Singer Artifact Collection

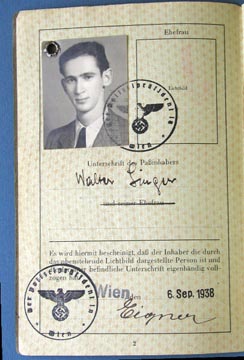

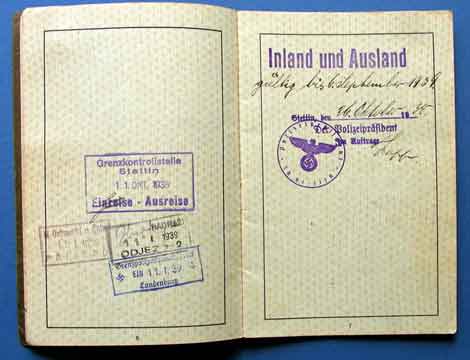

Walter A. Singer was married in Vienna on July 31, 1938, the last day that Jews were allowed to marry in Austria, which had been taken over by Hitler four months earlier. Shortly after their wedding, realizing that the Jews of Austria were in great danger, he and his wife Edith journeyed to the Baltic port (now Szczecin) from where they had booked passage to Latvia. According to Singer, Austrian Jews were aware of their danger long before German Jews. They sailed on a small, crowded fishing boat that carried 72 refugees.

Latvia, however, refused to admit so many Jews at one time, so although the boat was anchored in the port of Riga for three days while the Jews of the city pleaded with officials, they ended up having to sail back to Szczecin. With hindsight, Singer now feels they were fortunate, because Latvian Jews were to fare very badly later.

Knowing the Jews were returning, the Gestapo greeted the boat in Szczecin in late October and quartered the passengers in local Jewish homes.

Early in November, the stranded Jews were preparing to put on a play to raise money to return to their homes. On November 9, Singer went to the house of a 62-year-old man to get some phonograph records. That night, the Nazis unleashed their organized pogrom of Kristallnacht and the Gestapo arrived to arrest the older man but, perhaps out of kindness since he would not survive long, Singer speculates, they took the 22-year-old Singer instead.

He was transported to Sachsenhausen-Oranienburg, a concentration camp about 30 miles north of Berlin. Upon arrival, he was kept standing at attention outside with the other new arrivals for 48 hours while they listened to the screams of a recaptured escapee who was being tortured to death nearby. He was put to work building an airfield. The inmates were beaten with bullwhips and rifle butts as they worked.

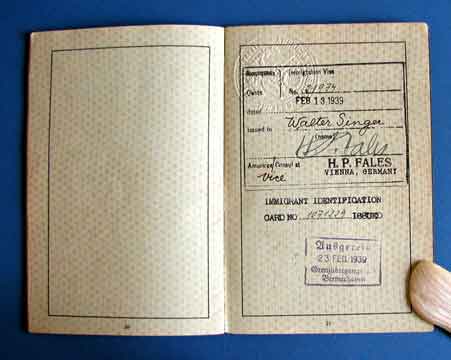

Edith, learning of his arrest, immediately went to the Gestapo to beg for her husband’s release. Even though she was continually thrown out and eventually threatened with arrest herself, she continued to dare to badger the Gestapo. They eventually said they would release him if she could present two steamer ship tickets out of Europe. She returned with two tickets for passage to the United States (not a small feat to be sure) and secured his release.

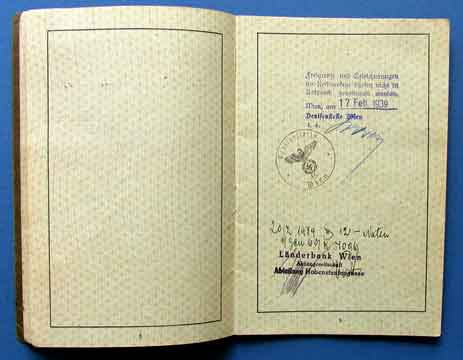

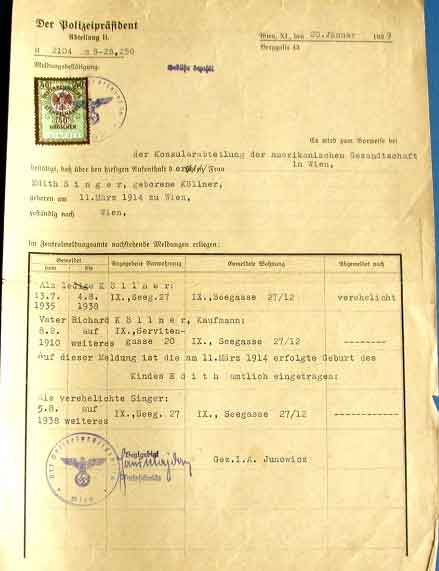

They went back to Vienna where they received American visas on January 6. They arrived in New York City on March 4, 1939. Of his wife, Walter said: “First of all, I loved her. Second of all, I owed her my life … so I try to fight twice as hard.”

“The importance of the [Cohen] Center is that we should never forget. It not only happened in the 1930s and 1940s, but it’s happened several times since then in other parts of the world … it’s not just that one time.”

– From an interview in The Monadnock Observer, July 21, 1984.

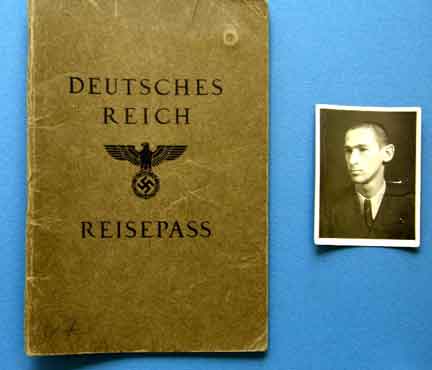

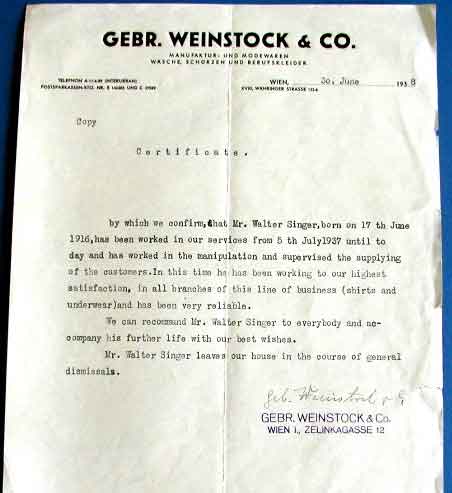

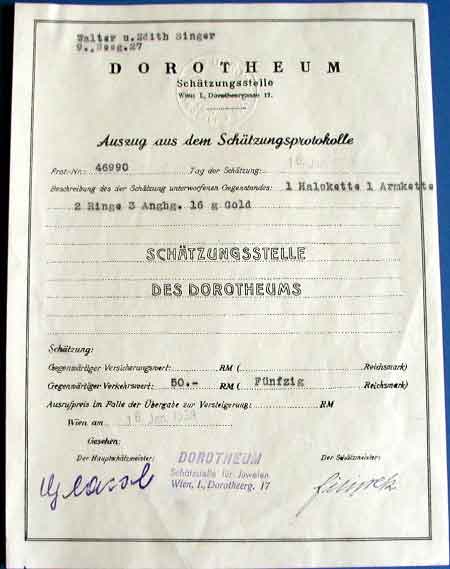

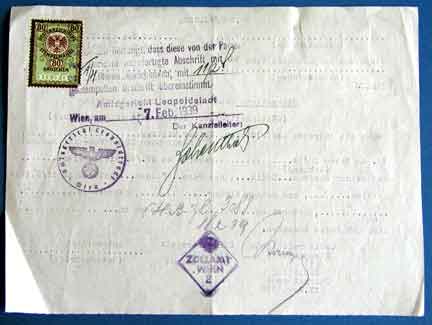

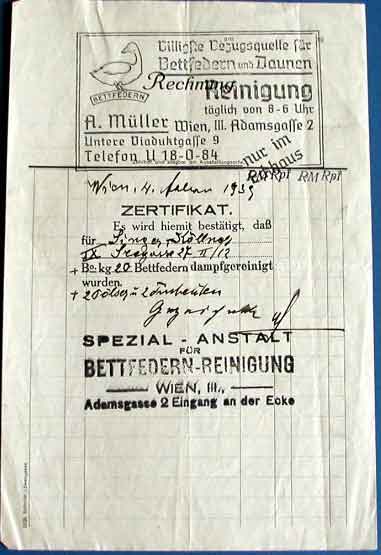

Documents in the collection

The following documents were donated to Dr. Charles Hildebrandt, founder of the Cohen Center for Holocaust Studies, by the Singer family. These documents illustrate some of the difficulties that were faced by would-be emigrants/immigrants. It is often asked: “Why didn’t Jews just leave?”

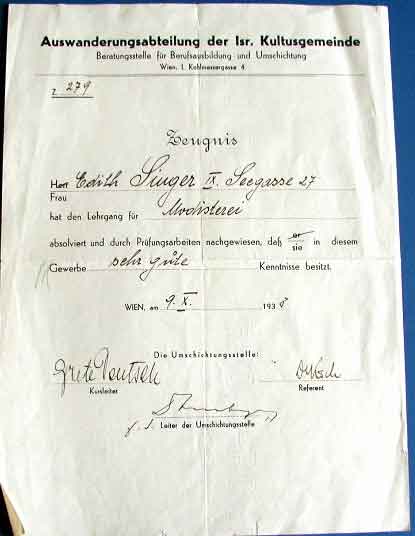

The documents will illuminate some of the difficulties in emigrating from Nazi Germany. Emigration required many things, not least among these, a sense of impending danger. Many Jews (less than .4% of the population by 1935) tried to accommodate their lives to the changes they faced daily. Many were patriots and veterans. Others were overwhelmed. If they decided to leave, where would they go? How would they get there? What was required of them if they did decide to uproot themselves? As often happened, Jewish women retrained themselves in order to make their emigration application more successful.

The documents will testify to the extreme difficulty faced by would-be Jewish emigrants from the Reich and potential immigrants to the United States.

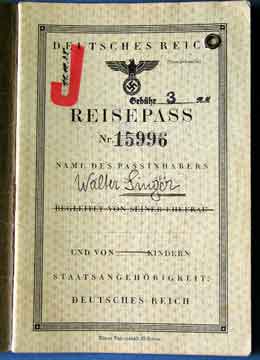

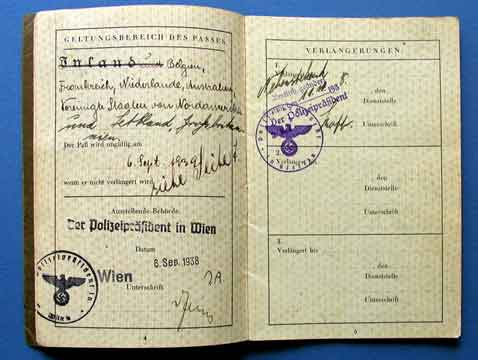

German Emigration Requirements

After 1937, Jews needed the following documents from German authorities to leave the country:

- Passport

- Certificate from the local police noting the formal dissolution of residence in Germany.

- Certificate from the Reich Ministry of Finance approving emigration. This certificate required:

- the payment of an emigration tax of 25 percent on total assets valued at more than 50,000 RM. This tax came due upon the dissolution of German residence.

- the submission of an itemized list of all gifts made to third parties since January 1, 1931. If their value exceeded 10,000 RM, then they were included in the calculation of the emigration tax.

- certification from the local tax office that there are no outstanding taxes due.

- certification from a currency exchange office that all currency regulations have been followed. An emigrant was permitted to take 2,000 RM or less in currency out of the country. All remaining assets were transferred into blocked blank accounts with restricted access.

- Customs declaration, dated no earlier than three days prior to departure, permitting the export of itemized personal and household goods. This declaration required:

- the submission of a list, in triplicate, of all personal and household goods accompanying the emigrant and their value. The lists must note items acquired to facilitate emigration.

- documents attesting to the value of personal and household goods and written explanations for the necessity of taking them out of the country.

- the certification from a currency exchange office permitting the export of itemized personal and household goods, dated no earlier than 14 days prior to departure. With the above documents, emigrants may leave Germany, if and only if they have valid travel arrangements and have entrance visas for another country. Note: After the union of Germany and Austria in March 1938, emigrants from Austria, holding an Austrian passport, had to apply for a German exit visa before they were permitted to leave the country.

U.S. Immigration Requirements

The information below was provided by Dr. William Meinecke, an historian at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. It is a list of documents that the United States government required before an applicant could secure a visa for immigration to the United States in the 1930s and 1940s.

The Visa application had to completed by American sponsors. The application was a two-sided document over four feet long. Six copies had to be submitted and no reasons were given to explain a rejection. If unsuccessful, the sponsor could not reapply for another six months.

Documentation Required for Immigration Visas to the United States

- VISA Application (Form BC) five copies

- Birth Certificate: Two copies (quotas are assigned by country of birth)

- Quota Number reached: (# established the person’s place on the waiting list to enter the United States)

- Two Sponsors, close relatives of prospective immigrant are preferred. The sponsors must be American citizens or have permanent status, and they must have filled out an Affidavit of Support and Sponsorship (Form C) six copies notarized, as well as provided:

- Supporting documents required of sponsors:

- Certified copy of most recent federal tax return

- Affidavit from a bank about accounts

- Affidavit from any other responsible person regarding other assets (affidavit from sponsor’s employer or statement of commercial rating)

- Certificate of Good Conduct from German Police Authorities, including two copies respectively of:

- Police dossier

- Prison record

- Military record

- Other government records about individual

- Affidavits of Good Conduct (After September 1940)

- Pass a Physical Examination at U.S. Consulate

- Proof of Permission to leave Germany (imposed September 30, 1939)

- Proof the prospective immigrant had booked passage to the western hemisphere (imposed September 1939)

These two documents illustrate some of the difficulties that were faced by would-be emigrants/immigrants. It is often asked: “Why didn’t Jews just leave?” This is a simplistic question with very complicated answers. The question is, of course, misdirected. Why do we ask the question? Is it that we assume that these people could somehow have done more to avert their victimization? By asking the question ,we miss the fundamental point that these were citizens of a modern nation-state.

Why should they leave their homes? How could they prophesize the future when even the most ardent Nazi could not foresee the “Final Solution” in 1938? If they decided to leave, how would they go? Where would they go? What was required of them if they did decide to uproot themselves?

The following attachments will testify to the extreme difficulty faced by would-be Jewish emigrants from the Reich and potential immigrants to the United States. When looking at what was required, it is important to remember that 1938 was a time before Xerox machines and e-mail.