Holocaust Survivor Passports Offer Intimate Lessons in History

You can read about history, or watch great documentaries, but nothing gives you a connection to the past like holding an old letter or historical document in your hand. For example, the students working on transcribing the letters of Willard Templeton, a New Hampshire soldier who fought and died in the Civil War, realized that touching those letters gave them a personal connection to a real person who participated in one of America’s great formative events. They came to know and like Templeton, so much so that they grieved when they learned of his death at the battle of Petersburg.

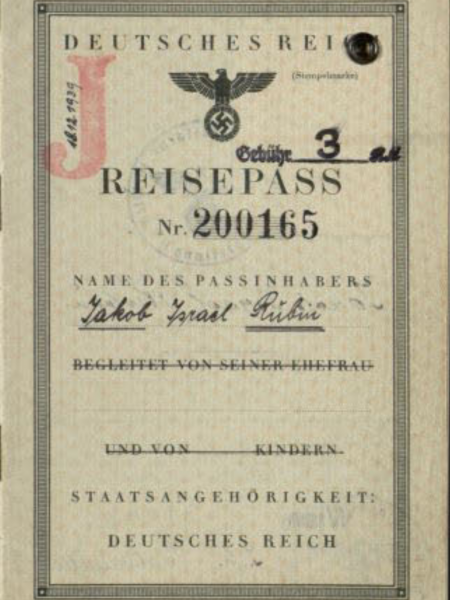

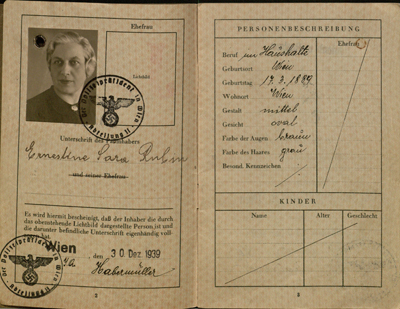

Realizing this power of primary sources, the Mason Library’s archivists, as part of their information literacy program, have developed a powerful exercise in which students are challenged to uncover as much information as they can about the lives and journeys of Holocaust survivors by examining their passports. “Basically, the exercise is to teach students how to do primary source research, make them comfortable using primary sources, and give them an appreciation for archival material,” explained the library’s Head of Special Collections and Archives Rodney Obien. “I break the students into groups and give each group a passport, but I don’t tell them anything about it. Then I ask them to delve into it and tell me as much as they can about the document and its former owner. They start with a passport that they usually can’t even read—it’s in German, and they’ve got to figure out how to unravel it’s message. When you do this kind of research, nothing’s prepared for you. You have to start with what you have and figure out what you can from the evidence at hand.”

The passports were issued in the 1930s in Germany, to Jewish citizens. The students can see the holder’s photo and birth date. And they can see the stamps that record when and where the holder traveled. Where was he or she going and why? The students are holding a record of a real person who held that same document, and their task is to create as much of a narrative of the person’s life as they can.

After each group has done its detective work on the individual passport, the class gathers to discuss the process and what they’ve learned. “This part of the exercise is really an essential piece of the process, because we can tie a lot of the information together and tease out an understanding that the students may not have noticed before,” said Assistant Archivist Brantley Palmer. “For instance, when we go around the class, students realize that all the passport holders have the same middle name (men were “Israel” and women were “Sara”). They wouldn’t realize that from working on an individual passport, but they see it when we go around the room. We discuss that the Nazi government changed Jewish citizens’ middle names on their passports as an additional way to identify them as Jewish (there’s also a large red “J” stamped on the front page of each passport). This leads to another discussion on the purpose of a passport. Many students feel that the document allows an individual to travel, but we see how its also a way for a government to keep tabs on its citizens and identify them. This exercise really helps students understand the weight of the history they’re holding in their hands.”

For Student Archives Assistant Mylynda Gill, the exercise not only taught her about real people during the Holocaust, but it also sparked an interest in research and archives that has landed her a prestigious internship at Dartmouth College. “I have now taught the exercise to my peers and got to experience them learning these things on their own,” she said.” This exercise did broaden my awareness of what individuals had to go through during this time. But it also taught me that it’s possible to use primary sources within my education.”

“There’s no better way to get students interested than through the active learning process of primary source research, and having documents as powerful as the Jewish Holocaust survivor passports really engages the students,” Palmer noted.