Knight Learns Life Lessons From Legendary Football Coach Bryant

KEENE, N.H. 10/22/10 - You don’t want to be around Henry “Hank” Knight when he’s watching the University of Alabama play football on TV.

“I typically don’t see it as a time I want to entertain friends or be entertained,” said Knight. “I want to be free to express my emotions. Friends tease me and say I’m somebody different when Alabama is on.”

In his third year as the director of Keene State’s Cohen Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies, Dr. Knight is also a die-hard Alabama fan, rolling with the Tide’s up-and-down fortunes on the gridiron. Knight’s allegiance to Alabama can be expected. After all, he was born in Alexander City, Ala., a hotbed for college football where passion for the Crimson Tide and the rival Tigers of Auburn University runs high. Knight’s devotion to the Crimson and White also follows family lines. Both his father Floyd and mother Wanda were UA grads. But Knight’s affection for Alabama goes far beyond the lofty accomplishments of the team. A 1970 graduate of Alabama, Knight had the privilege to play for legendary coach Paul “Bear” Bryant. “Coach Bryant had this mystique about him that was larger than life. Almost every one of us loved him and feared him at the same time,” he said.

While Knight can talk for hours about the innovations that Bryant brought to the game, he was equally impressed with his meticulous organization skills. Practices, broken down into small groups, were crisp with no wasted time, and a high priority was placed on teamwork or what Bryant called “oneness.” A proper tackle called for 11 players converging and hitting someone at once.

Knight also marveled at Bryant’s sense of timing, his ability to mentor his coaches, and, most important, his relationship with his players. In his private sanctuary - a tower right in the middle of practice - he didn’t miss anything. And when he lifted his megaphone to his lips and called your name, it was the like God calling you from above.

“You got a sense that he was always watching,” said Knight. “And when you thought you didn’t count or didn’t matter - that’s when he somehow had the knack of letting you know you did.”

It would have been understandable if Knight had been overlooked. Because his dad worked for the federal government, Knight had moved around while growing up, spending a good deal of his childhood in Aiken, South Carolina, and going to high school in Gaithersburg, Maryland. It wasn’t until high school that he started to think about playing college ball.

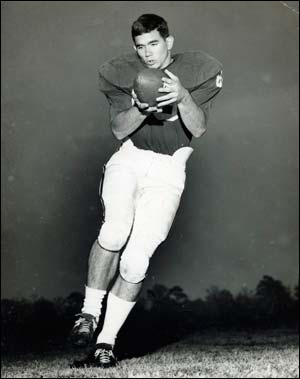

A high school coach who had played for Bryant got Knight an invitation to join the Alabama team as a walk-on. “I went down knowing I was small, but from my perspective quick enough to play at Alabama,” said Knight. “They were noted for having smaller players.” A pulling guard who also played linebacker and defensive end in high school, Knight was moved to a defensive back or the rover position, and even saw time at wide receiver at Alabama. Knight said he was in awe of the fact he was joining an Alabama team that had won consecutive national championships (1964 and 1965) prior to his arrival.

Looking to make a name for himself as a freshman, Knight, near the end of a spring practice, was able to make a crunching tackle that caught the eye of Bryant. Calling the players around him, Bryant said, “We do things like that, we end with perfection.”

Knight went from as high as a kite to completely crushed the following week when he got overlooked and didn’t play in the team’s Red & White spring game. Out in the parking lot following the game, Knight suddenly felt an arm around his shoulder. “I turned around and it was Coach Bryant,” said Knight. “He winked and said, ‘It’s OK. I understand. Hold your head up.’”

“I was a walk-on. I was a scrub. But I was able to learn the values that were essential to Coach Bryant,” said Knight. “I was tremendously impacted by what I learned about working with people and what I learned about values and teamwork.”

Hank Knight got hurt at the end of his sophomore season and never played a varsity football game for Alabama. Although he went on to play baseball for Hall of Famer Joe Sewell at the school, the lessons he learned from Bryant stay with him today.

The fall before Bryant died in January of 1983, Knight renewed correspondence with his former football coach. By then a professor of religious studies and college chaplain at Baldwin-Wallace College in Ohio, Knight, who had become strongly committed to nonviolent forms of conflict resolution, was having trouble reconciling himself to the violence in the sport.

“Coach Bryant was probably the finest teacher I’d ever been around, and I had learned so much about teamwork and oneness from him. I had figured out ways to incorporate his lessons into my own work on campus, but I had never told him any of this,” Knight said.

Among Knight’s readings at the time, an article entitled “Loving to win and hating to lose” stood out. The message: You don’t define yourself by an outcome of a game, you define yourself by who you are. It resonated with him.

“All those things Coach Bryant was doing were life lessons - trying to help us be true winners,” said Knight. “If we played poorly but won, he might say, ‘They lost - you didn’t win.’ Or he might put the blame on his own shoulders after a difficult loss, saying, ‘Hold your heads up - I lost. It was poor coaching. You were winners.’”

Knight wrote Bryant a long letter about how young people develop a sense of who they are. To his surprise, he received a personal reply from Bryant. “In a sense, I got to thank him for everything I learned,” said Knight. “By January he was gone. I was awfully lucky.” Following Bryant’s death, Knight wrote a condolence note to the family and recalled the incident in the parking lot when Bryant came out to console him. “That’s the Coach Bryant I remember,” said Knight. “I was a nobody, but not to him.”