One Family’s Story: Peter Eisenstadter

November 9, 2000

This article is adapted from an address given at Larracey Auditorium, Keene Middle School in observance of Kristallnacht.

On November 9, 1938, it was calm in my father’s neighborhood in Berlin, Germany. The Jews were all under curfew, so the streets were quiet. The stillness was broken when my father’s upstairs neighbor was arrested for being out late. My father remembered how his neighbor’s wife screamed as they took them away. He later found that they had been sent to Sachsenhausen concentration camp, but there was a relatively happy ending to this story. Both were released some months later and subsequently fled Germany to safety. Kristallnacht left comparatively little impact on this block. But the date always reminded my father of a November three years later, when he learned of his own father’s fate.

From early childhood, I have heard the number- six million. Six million Jews. Six million victims of the Holocaust. But it is not possible to identify with a number, especially a number that large. For me, that number has always worn one face.

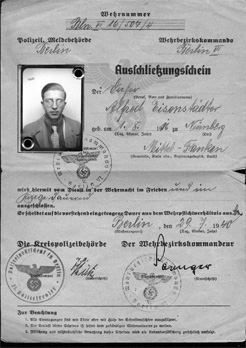

I own a small photograph of a studious-looking man, with spectacles, high collar, prim appearance, serious expression. He is Dr. Julius Eisenstadter, my phantom grandfather. We never met; he died four years before I was born. I only know a few things about him. He was a high school professor of language and history; an author of historical works, educational articles, and studies of comparative mythology. He had served as a member of the City Council of Nuremberg. There had been no room for him in the quota for America. He had had to be left behind when my father and his mother left Germany in what my father always believed was probably the last trainload of Jews out of Germany in 1940. My father learned in November, 1941, that his father had been deported and had disappeared without a trace. It was a guilt he carried all of his life. I often wondered if he felt he had traded his father for the family he made in America. All his efforts to bring his father across had come to nothing. What else could he have done? Realistically, and with the hindsight of history, nothing. The ancient Greeks would have called it Fate.

His only legacy is his last postcard from Germany. The handwriting is very close and small; I cannot read it or translate it. I never had the heart to ask my father to do it. Now, no one can.

There is one other legacy, in a way. Education has become the family profession. Like my father and grandfather before me, I became a high school teacher. My specialty was language arts, and I taught mythology for many years.

All my life, I have been aware of a strange personal irony: if there had been no war, there would have been no me. I share this irony with many of my generation who are children of refugees. I am the first American born in my whole family. My bar mitzvah, in 1958, was the first of many others. But what I did not understand until many years later about this celebration was that it was also a survival celebration. Another guest of honor had been invited, my mother’s uncle Joseph Rubin, alas now too ill to attend. He had saved all of his brothers and their families, bringing them over as he could. The number included my other grandfather, Jacob, a World War I combat veteran of the Austrian Mountain Artillery, whose medals could not help him and would not have saved him.

It seems that I was born to bear witness. If there had been no war, there would be no need. But I take my very existence from the fact of this war. So I have somehow, almost unaware, taken on the responsibility of telling this story. And there is also, for me, a darker recognition. In the midst of a very rich life, accompanied by a beautiful and accomplished wife and two sons who are my constant pride and joy, surrounded by my Christian neighbors and friends, both colleagues and students, respected in my profession, and safe in the United States– there is nevertheless a small, very small place in the back of my mind, of doubt, of mistrust. One little space– where I keep a metaphorical suitcase packed. Can’t it happen here? It has already happened here. Here- and everywhere else.

This has been a century littered with genocides: 1 1/2 million Armenians; millions of Ukrainians and others under Stalin; the 6,000,000 Jews, 24,000,000 Russians, all the rest- 55 million and more in World War II; 1-2,000,000 in Cambodia; 3/4 of a million in Rwanda; Bosnia and Kosovo with their mass graves and concentration camps; the horror of Darfur. All this, backed up against our own bitter history in the previous century, of the uncounted lost in the vicious institution of African slavery and the genocidal near-extermination of the Native-American population. We Jews have become, through our own suffering, a kind of metaphor ourselves for all these and more. Singled out as we are, we find our experience, the symbol of all the rest, is not entirely unique.

There is, however, one significant difference. As horrendous and infamous as all these genocides are, we Jews are still the only group whose fate was the end product of an industrial process specifically designed for our complete extermination. We are, to my knowledge, the only ones to undergo this particular version of genocide. With the ruthless factory efficiency that only the twentieth century could finally provide, the victims were gathered, transported, catalogued, sorted, selected, destroyed, and either completely eliminated or, in many cases, even recycled as products for human consumption. At some point, it may be possible to imagine that there was no longer a question even of malice involved. The process had simply become automatic, like all good industrial operations. Think of the kind of dehumanization of innocent individuals that made such things possible: people as raw material for the manufacture of death and the occasional consumer products. I have said that our Holocaust has become the symbol of genocide; what must we do in an often violent world to see to it that we do not become the pattern?

Well, is the lesson never to be learned? Only the insane cycle of rage, regret, and repentance- until next time? Is our “Never Again” to become “every so often”? Even now, in Israel itself, people can only remember their mutual hatred, rather than their commonality. Where will this end? How can it end? And what will happen if it doesn’t?

The history of the last hundred years is thick with ghosts. And murder, as Shakespeare said, “will speak with most miraculous organ.” Like Hamlet’s father, my phantom grandfather is heard, saying “Adieu, adieu. Remember me.” But the message is not a desire for revenge. Have we not had enough of that? Rather, is not the message that we are all alive and just want to live? That there is such a thing as respect for our common humanity? This may be a new millennium, but the message is as old as the prophets: Hineh ma tov uma naim shevet achim gam yachad. Which in today’s climate may be freely translated as, “See how good it is when people live together as kindred.”